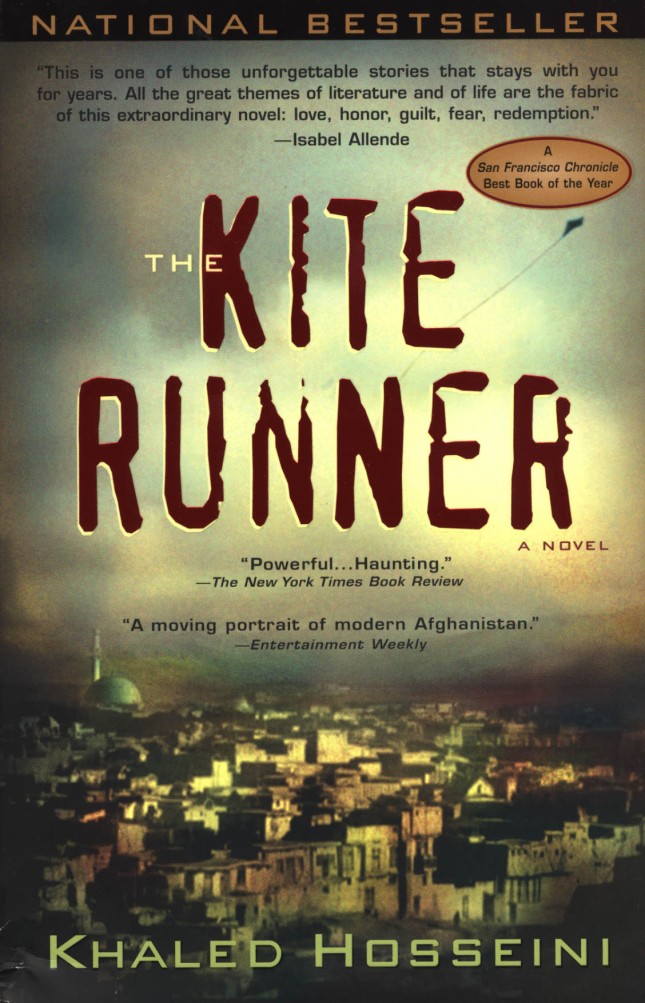

Here’s a bit from a very detailed article in the Afghan magazine. It tells you about the novel and has theme quotes and an interview link.

The Kite Runner is an Afghan novel that is one of its kind. Like no other, it reads like a confessional, yet laced with thrills and emotion. Or is it an Afghan novel? Many would say that since, it is written in English, and by an Afghan who has spent over 20 years in the United States, it cannot be Afghan. The author is too vulnerable and self-reflective. And, moreover, he is living in America, so what can he write about Afghanistan?

The novel has received great reviews by literary editors around the world. One Afghan says, “As I read it, I thought I was reliving my childhood.” This novel is clearly about Afghanistan and the story of an Afghan who finds his way out of a personal, guilty past, or as the author says, “my past of un-atoned sins”.

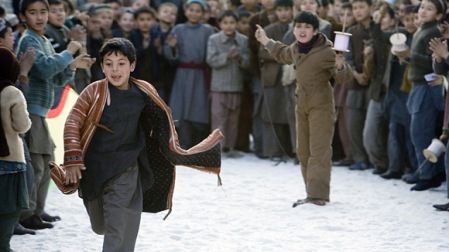

It should be welcomed by the Afghan people and definitely deserves to be translated into Dari and Pashto. Whether or not the novel is based on true experience – the annual kite-flying contest, on which the entire story is built, is fictional – it is a self-analyzing confession of personal failure. Written in the first person, makes it all the more reflective. At the same time, it is exciting reading, and filled with emotions.

In some ways, The Kite Runner is a reversal of Akram Osman’s short story, “The Hero and the Coward”, a standard story where the main character is presented as a hero – as the title itself reflects. In The Kite Runner, Amir, the main character, tells his own story, a story of how he has been a coward all his life. Ironically, he comes from the dominating heroic tribe, but he gradually begins to realize the weaknesses and flaws in himself. In contrast, the hair-lipped, Hazara servant-friend turns out to be not only a courageous hero, but also a true ‘jawanmard’ who dispenses kindness even to those who are not worthy of it.

CHILDHOOD IN KABUL

The first section of the novel reflects Amir’s childhood in Kabul during the 1960’s and 70’s. Although his relationship with Hassan is far from noble, yet the two spend many wonderful days together. Amir’s greatest pain is trying to find approval from his wealthy, patronizing father. These two motifs – his friendship with Hassan and his detached relationship with his father – come to a climax at the annual kite-flying contest in Kabul. This would be his day of salvation, when he could prove to his father that he is worthy of recognition. But it would also be the day when his friendship with Hassan changes forever.

Almost unexpectedly, Amir emerges as the champion in the kite-flying contest, but the victory is bittersweet. He has to produce the fallen kite. If not, his father will not acknowledge him as the champion. Hassan, an expert kite runner, knows how important the kite is and so heedlessly pursues it. He finds it in a lonely alley, but here the villain, Aseef – who is a caricature of crass evil – catches up with Hassan. Aseef hates Hassan because of his background. Also, earlier Hassan had threatened Aseef with his slingshot when Aseef was about to beat up Amir. But rather than running for his life, Hassan clings to the kite for Amir’s sake. When Amir finds Hassan being helplessly abused by Aseef, he remains in hiding less Aseef notices him. He must produce that kite for his father. And here is the terrible irony. As Hassan is sacrificing himself for Amir, Amir secretly betrays his friendship with Hassan simply by ignoring him. It pains him as he does so, and he recalls the helpless lambs on Eid-i Qurban, who have to die “for a higher purpose” (67). Now, he too “hands Hassan over to the slaughter”, so that he can emerge as a hero in his father’s eyes. He rationalizes, “Maybe Hassan was the price I had to pay, the lamb I had to slay, to win Baba” (68).

But Amir knows he is no champion. He is fully aware of his shameful betrayal but he cannot confess it. He denies it, and he suddenly realizes he will get away with it. “‘I watched Hassan get raped,’ I said to no one. A part of me was hoping that someone would wake up and hear, so I wouldn’t have to live with this lie anymore. But no one woke up and in the silence that followed, I understood the nature of my new curse: I was going to get away with it” (75). To his horror, he realizes he can sin with impunity, and this is the damning truth that will haunt him for the rest of his life – the curse of un-forgiven sin.

Read the rest here.