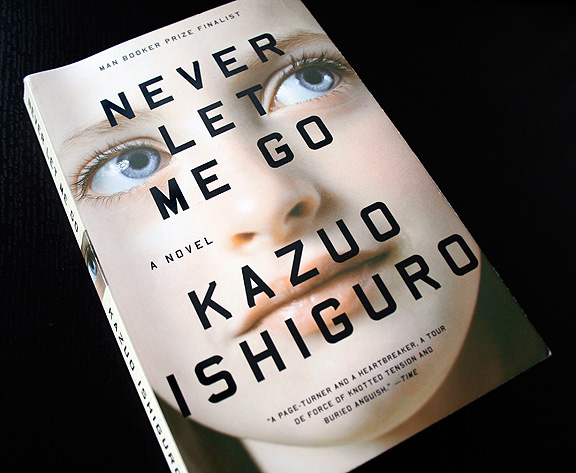

It’s no secret that I love Margaret Atwood and I have found her take on Kazuo Ishiguro’s ‘Never Let Me Go’. Her review is entitled ‘Brave New World’ and she explains why she found the novel really chilling. It is a very interesting read.

Never Let Me Go is the sixth novel by Kazuo Ishiguro, who won the Booker Prize in 1989 for his chilling rendition of a bootlickingly devoted but morally blank English butler, The Remains of the Day. It’s a thoughtful, crafty, and finally very disquieting look at the effects of dehumanization on any group that’s subject to it. In Ishiguro’s subtle hands, these effects are far from obvious. There’s no Them-Bad, Us-Good preaching; rather there’s the feeling that as the expectations of such a group are diminished, so is its ability to think outside the box it has been shut up in. The reader reaches the end of the book wondering exactly where the walls of his or her own invisible box begin and end.

Ishiguro likes to experiment with literary hybrids, to hijack popular forms for his own ends, and to set his novels against tenebrous historical backdrops; thus When We Were Orphans mixes the Boys’ Own Adventure with the ’30s detective story while taking a whole new slice out of World War II. An Ishiguro novel is never about what it pretends to pretend to be about, and Never Let Me Go is true to form. You might think of it as the Enid Blyton schoolgirl story crossed with Blade Runner, and perhaps also with John Wyndham’s shunned-children classic, The Chrysalids: The children in it, like those in Never Let Me Go, give other people the creeps.

The narrator, Kathy H., is looking back on her school days at a superficially idyllic establishment called Hailsham. (As in “sham”; as in Charles Dickens’ Miss Havisham, exploiter of uncomprehending children.) At first you think the “H” in “Kathy H.” is the initial of a surname, but none of the students at Hailsham has a real surname. Soon you understand that there’s something very peculiar about this school. Tommy, for instance, who is the best boy at football, is picked on because he’s no good at art: In a conventional school it would be the other way around.

In fact, Hailsham exists to raise cloned children who have been brought into the world for the sole purpose of providing organs to other, “normal” people. They don’t have parents. They can’t have children. Once they graduate, they will go through a period of being “carers” to others of their kind who are already being deprived of their organs; then they will undergo up to four “donations” themselves, until they “complete.” (None of these terms has originated with Ishiguro; he just gives them an extra twist.) The whole enterprise, like most human enterprises of dubious morality, is wrapped in euphemism and shadow: The outer world wants these children to exist because it’s greedy for the benefits they can confer, but it doesn’t wish to look head-on at what is happening. We assume—though it’s never stated—that whatever objections might have been raised to such a scheme have already been overcome: By now the rules are in place and the situation is taken for granted—as slavery was once—by beneficiaries and victims alike.

All this is background. Ishiguro isn’t much interested in the practicalities of cloning and organ donation. (Which four organs, you may wonder? A liver, two kidneys, then the heart? But wouldn’t you be dead after the second kidney, anyway? Or are we throwing in the pancreas?) Nor is this a novel about future horrors: It’s set, not in a Britain-yet-to-come, but in a Britain-off-to-the-side, in which cloning has been introduced before the 1970s. Kathy H. is 31 in the late 1990s, which places her childhood and adolescence in the ’70s and early ’80s—close to those of Ishiguro, who was born in 1955 in Nagasaki and moved to England when he was 5. (Surely there’s a connection: As a child, Ishiguro must have seen many young people dying far too soon, through no fault of their own.) And so the observed detail is realistic—the landscapes, the kind of sports pavilion at Hailsham, the assortment of teachers and “guardians,” even the fact that Kathy listens to her music via tape, not CD.

Kathy H. has nothing to say about the unfairness of her fate. Indeed, she considers herself lucky to have grown up in a superior establishment like Hailsham rather than on the standard organ farm. Like most people, she’s interested in personal relationships: in her case, the connection between her “best friend,” the bossy and manipulative Ruth, and the boy she loves—Tommy, the amiable football-playing bad artist. Ishiguro’s tone is perfect: Kathy is intelligent but nothing extraordinary, and she prattles on in the obsessive manner touchy girls have, going back over past conversations and registering every comment and twitch and crush and put-down and cold shoulder and gang-up and spat. It’s all hideously familiar and gruesomely compelling to anyone who ever kept a teenage diary.

In the course of her story, Kathy H. solves a few of the mysteries that have been bothering her. Why is it so important that these children make art, and why is their art collected and taken away? Why does it matter to anyone that they be educated, if they’re only going to die young anyway? Are they human or not? There’s a chilling echo of the art-making children in Theresienstadt* and of the Japanese children dying of radiation who nevertheless made paper cranes.

What is art for? the characters ask. They connect the question to their own circumstances, but surely they speak for anyone with a connection with the arts: What is art for? The notion that it ought to be for something, that it must serve some clear social purpose—extolling the gods, cheering people up, illustrating moral lessons—has been around at least since Plato and was tyrannical in the 19th century. It lingers with us still, especially when parents and teachers start squabbling over the school curricula. Art does turn out to have a purpose in Never Let Me Go, but it isn’t quite the purpose the characters have been hoping for.

One motif at the very core of Never Let Me Go is the treatment of out-groups, and the way out-groups form in-groups, even among themselves. The marginalized are not exempt from doing their own marginalization: Even as they die, Ruth and Tommy and the other donors form a proud, cruel little clique, excluding Kathy H. because, not being a donor yet, she can’t really understand.

Read the rest here.