Monthly Archives: April 2012

Knew it!

Characters of The Crucible: Abigail Williams

Race, Violence, Kids: Watching ‘Hunger Games’ with My 10-Year-Old Son

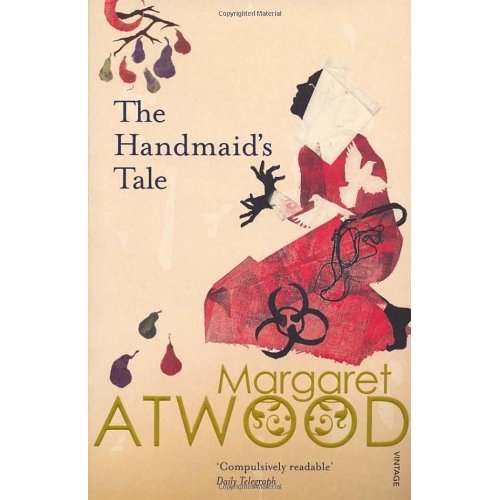

A good discussion of The Hunger Games and speculative fiction. The Handmaid’s Tale is speculative fiction and you may find this worth reading.

The best works of speculative fiction can take aspects of the present to far-reaching extremes that are simultaneously familiar yet disturbing, offering us a magic lens that renders visible the machinations and ultimate repercussions of social, economic and political forces around us.

In a dystopian, post-apocalyptic North America, 16-year-old protagonist, Katniss, is one of two-dozen teenaged participants representing the country’s 12 districts in an annual gladiatorial battle to the death conducted in a specially designed arena. It is no coincidence that the country where the Hunger Games are held is named “Panem.” Commemorating a failed rebellion by the districts against the Capitol, the televised spectacle serves as part of the futuristic state’s policy of “bread and circuses” or “panem et circenses,” as originally referred to by first century satirist and poet Juvenal writing about ancient Rome’s strategy to distract, appease and control the populace.

The futuristic world in The Hunger Games seems utterly believable, the logical extension of a voyeuristic, consumerist culture, where significant segments of the population are obsessed with reality television and celebrity news, while sticking their heads in the sand about the blatant social, political and environmental problems going on around them. The marked contrast between the extravagant Capitol and the impoverished districts in the Hunger Games is no less stark and no less unjust than the economic stratifications and disparities that exist today. As for exploiting children, cage matches with boys as young as eight fighting in front of sold-out adult audiences were held in England last year.

Suzanne Collins’ bestselling young adult trilogy is a definitely page-turner. But I hesitated about going to the film. Meanwhile, my 10 year-old begged me to see it. He’d already raced through the first two books of the Hunger Games trilogy twice, reading the last one four times. I’d thoroughly enjoying them too, and was reminded of the speculative fiction I’d devoured when I was a teenager — Brave New World, 1984, The Chrysalids, Dune.

Read the rest here.

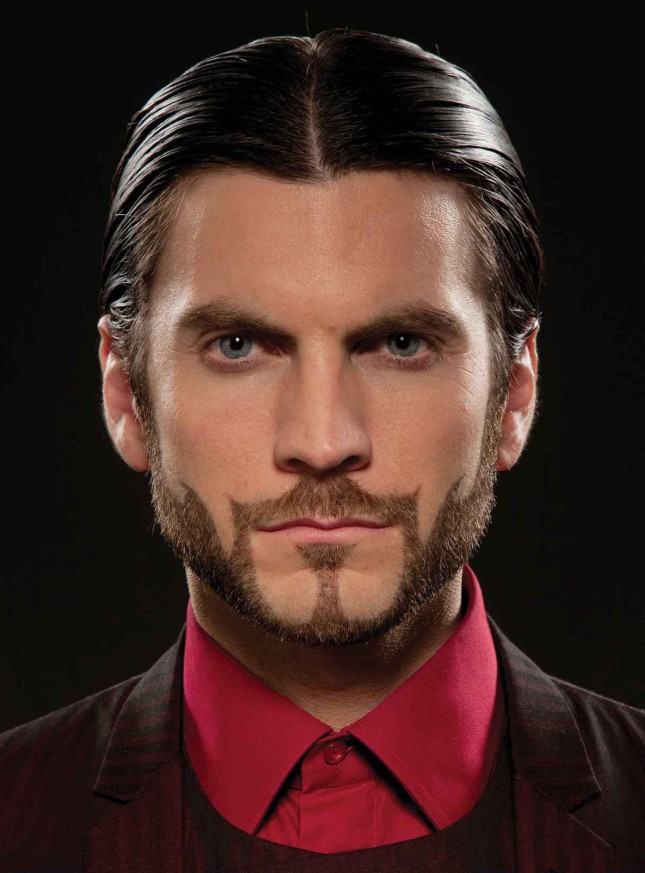

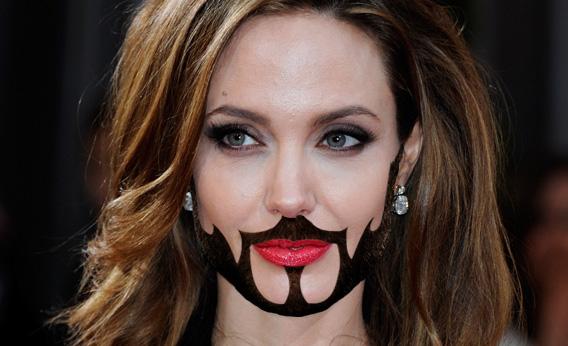

Everything is Better with Seneca’s Beard from The Hunger Games

If you have seen The Hunger Games movie you cannot fail to notice Seneca’s (The Gamemaker) beard. Observant viewers will also notice that Seneca is played by Wes Bentley (Ricky in American Beauty). Over at Slate they think that more people should consider sporting Seneca’s finely trimmed whiskers. To help everyone get started, they’ve created a handy cutout, plus some examples for how to use them. Go here to find them.

Feminism and The Handmaid’s Tale

An interesting article from Jennifer Dean.

Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale would seem, on the surface, a straightforward feminist text. The narrative is set in a speculative future, exploring gender inequalities in an absolute patriarchy in which women are breeders, housekeepers, mistresses, or housewives—or otherwise exiled to the Colonies. In Atwood’s fictional Gilead, all of the work of twentieth-century feminism has been utterly undone, and the text explores the effects of this from a first-person point of view that elicits the reader’s sympathy. Offred’s tale functions as a critique of women’s oppression, as we can see from one of her earlier statements problematizing biological determinism: “I avoid looking down at my body, not so much because it’s shameful or immodest but because I don’t want to see it. I don’t want to look at something that determines me so completely” (72-73). Yet Offred’s story is neither wholly triumphant nor wholly straightforward. Offred’s narrative is potentially undermined, and certainly deconstructed, by the future historians featured in the text’s epilogue. At the same time, Offred herself is an unreliable and elusive narrator. Can we believe her story? And does her unreliable status enhance or detract from the text’s feminist messages? In raising these questions, Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale engages with the debates of feminist politics, dramatizing a complicated and ongoing ideological history. This is a complex novel, one that is open to more than one interpretation, but there are certain affinities with some of the major developments in feminist thought in the twentieth century, from Virginia Woolf’s arguments about women’s roles and women’s writing to later discourses on the male gaze, the binary division of male and female, and the radical potential of language.

Read more here.

Encountering Conflict in The Crucible

Through our study of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible you will become aware of Arthur Miller’s links to Salem and the witch hunts and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) McCarthy hearings of the 1950s. However, the text explores more than just the conflict between the ‘accusers’ and the ‘accused’. Think about the different types of conflict seen in the play. The idea that ‘ignorance’ fuels conflict is apt, as ignorance is masked behind the Law and God. To study the play successfully you need to think conceptually about conflict, how conflict can manifest itself and the factors that can ‘shape’ our responses to conflict.

The fear that lies at the heart of the townspeople is based on a religious fundamentalism in which God is seen as the determiner of one’s life. The presence of God implies the presence of the Devil and the townspeople of Salem see His workings in the young and vulnerable girls ‘who danced in the woods’.

John Proctor is also condemned because of his ‘weakness’. The idea that conflict can be ‘fuelled’ by ignorance has a particular link to the play as Proctor cries ‘A fire, a fire is burning! I hear the boot of Lucifer, I see his filthy face…For them that quail to bring men out of ignorance, I have quailed, and as you quail now when you know in all your black hearts that this be fraud – God damns our kind especially, and we will burn, will we’ll burn together!’

It is ironic that Reverend Parris says ‘I am not blind; there is a faction and a party’ as his greed and self-interest put him in conflict with his position as minister. He is morally weak and openly divisive. He is a hypocrite and a coward – not qualities linked to a good ‘man of God’. The conflict comes, not from within but because he manipulates the townspeople into believing that piety equals obedience, ‘There is either obedience or the church will burn like Hell is burning!’

Again, it is essential that an understanding of ‘ignorance’ is clear within your writing. This play presents ‘ignorance’ as faith and belief – a belief that God ‘will watch over us’. Then there is the ‘ignorance’ of youth – that presented by the young girls, including Abigail. Hale says to Tituba, ‘You are God’s instrument put in our hands to discover the Devils’ agents among us.’ The fear of retribution that stems from a lack of knowledge and maturity allows the elders to manipulate the young girls.

Adapted from The Age.

The Handmaid’s Tale in pictures

“I said there was more than one way of living with your head in the sand and that if Moira thought she could create Utopia by shutting herself up in a women-only enclave she was sadly mistaken. Men are not just going to go away, I said. You couldn’t just ignore them.”

A new Folio Society edition of Atwood’s landmark dystopian novel is accompanied by striking illustrations from Anna and Elena Balbusso. Go here to see more.

Margaret Atwood: Haunted by The Handmaid’s Tale

It has been banned in schools, made into a film and an opera, and the title has become a shorthand for repressive regimes against women.

Margaret Atwood has said about her book, “Some books haunt the reader. Others haunt the writer. The Handmaid’s Tale has done both.” Here she discusses her book and its impact –

The Handmaid’s Tale has not been out of print since it was first published, back in 1985. It has sold millions of copies worldwide and has appeared in a bewildering number of translations and editions. It has become a sort of tag for those writing about shifts towards policies aimed at controlling women, and especially women’s bodies and reproductive functions: “Like something out of The Handmaid’s Tale” and “Here comes The Handmaid’s Tale” have become familiar phrases. It has been expelled from high schools, and has inspired odd website blogs discussing its descriptions of the repression of women as if they were recipes. People – not only women – have sent me photographs of their bodies with phrases from The Handmaid’s Tale tattooed on them, “Nolite te bastardes carborundorum” and “Are there any questions?” being the most frequent. The book has had several dramatic incarnations, a film (with screenplay by Harold Pinter and direction by Volker Schlöndorff) and an opera (by Poul Ruders) among them. Revellers dress up as Handmaids on Hallowe’en and also for protest marches – these two uses of its costumes mirroring its doubleness. Is it entertainment or dire political prophecy? Can it be both? I did not anticipate any of this when I was writing the book.

Read the rest at The Guardian website.

Arthur Miller’s The Crucible: Fact & Fiction

Arthur Miller wrote a “Note on the Historical Accuracy of this Play” at the beginning of the Viking Critical Library edition:

This play is not history in the sense in which the word is used by the academic historian. Dramatic purposes have sometimes required many characters to be fused into one; the number of girls involved in the ‘crying out’ has been reduced; Abigail’s age has been raised; while there were several judges of almost equal authority, I have symbolized them all in Hathorne and Danforth. However, I believe that the reader will discover here the essential nature of one of the strangest and most awful chapters in human history. The fate of each character is exactly that of his historical model, and there is no one in the drama who did not play a similar – and in some cases exactly the same – role in history.

As for the characters of the persons, little is known about most of them except what may be surmised from a few letters, the trial record, certain broadsides written at the time, and references to their conduct in sources of varying reliability. They may therefore be taken as creations of my own, drawn to the best of my ability in conformity with their known behavior, except as indicated in the commentary I have written for this text. (p. 2)

Read more here.